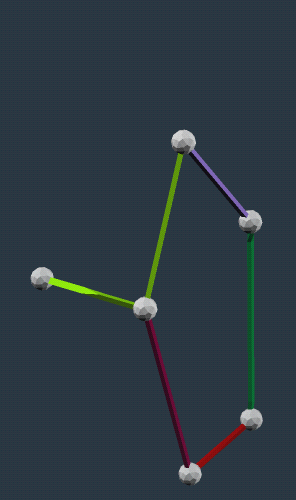

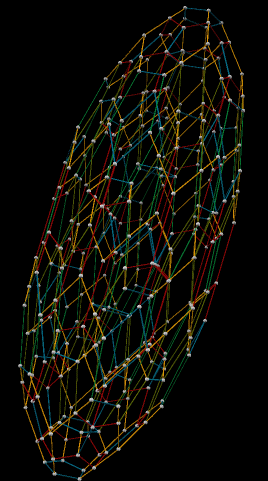

Any two non-parallel vectors determine what I call an "affine-regular" pentagon. In such a pentagon, we relax the condition of equal angles and sides, but retain other important characteristics of a regular pentagon. Specifically, each diagonal of the pentagon (a pentagram edge) is still parallel to one side of the pentagon, and has a length equal to that side's length times tau, the golden ratio. The result is as if we had applied a particular affine transformation to a regular pentagon, making it look stretched and skewed... but parallel lines are still parallel (the definition of affine!).

|

|

Several such pentagons can be constructed with Zome; infinitely many can be built with vZome. The construction can be performed laboriously with any recent version of vZome, using translation symmetry and "Phi divide", or with a single command since vZome 2.1. To use that command, simply select any two struts that share a ball, and select "Affine Pentagon" from the "Construct" menu.

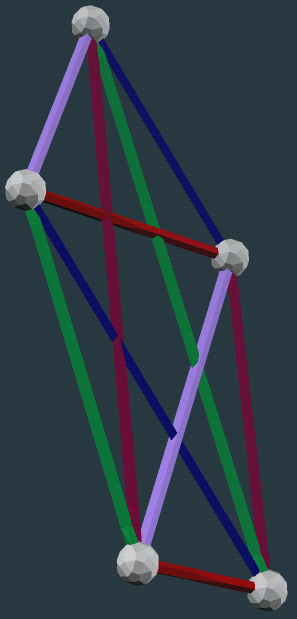

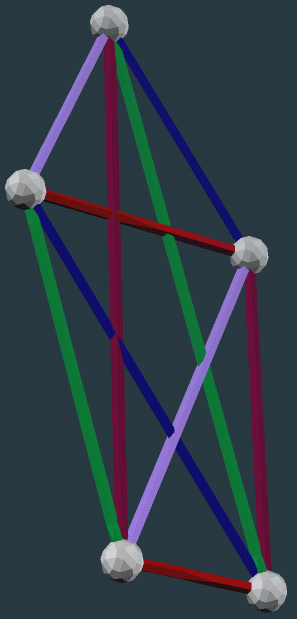

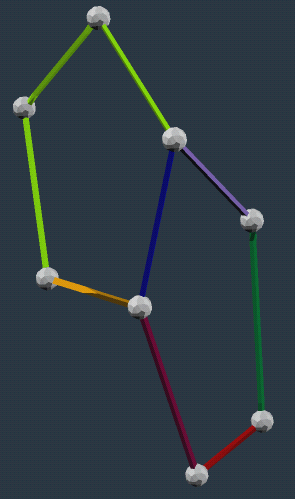

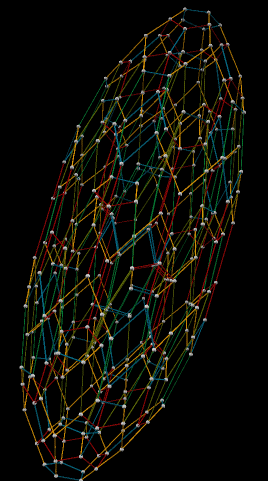

The concept of affine-regular pentagons is interesting, but it doesn't stop there. It turns out that three non-coplanar vectors determine an affine-regular dodecahedron. You can try this with vZome to convince yourself. Here's an example:

|

|

To try this, construct an affine-regular pentagon as described above. Build any strut from one of its vertices, as long as you don't build in the same plane as the pentagon. Now select the new strut, and one of its old neighbors, and use "Affine Pentagon" again. Now the only choices you have to make are which face to build next. Wherever you find a vertex with only two pentagons, fill in the third; before you know it you've built up an entire affine-regular dodecahedron.

|

|

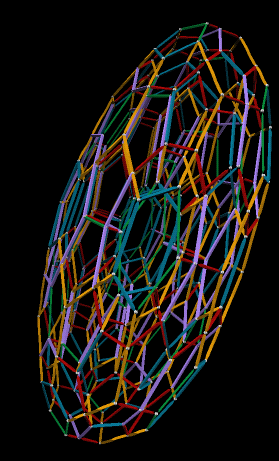

Two, three... what about four vectors? Yes, it appears that four vectors determine an affine-regular 3D projection of a 120-cell. (I haven't proved this, but experimentation seems to indicate it, and it seems reasonable.) The procedure is identical to what I just described, except when you're done with the dodec, choose a vertex and drag out a fourth strut, on the exterior of the dodec. That strut will determine three more pentagons, and by extension, the whole 120-cell. (Don't drag out any more struts, just use "Affine Pentagon" and sometimes "Join Balls".) You want to surround each vertex with four struts, and six pentagons, each pentagon sharing two struts, until you get to the surface of the 120-cell where things may coincide.

|

|

You'll always get some kind of ellipsoid, whose shape is determined by the four starting vectors. You can easily get an ellipsoid with rotatational symmetry, either on purpose or by accident. One way to do it on purpose is to start with an affine-regular dodecahedron that has rotational symmetry, like one of those found in the normal 120-cell, and look for a fourth vector that preserves that symmetry as you build on the additional pentagons.

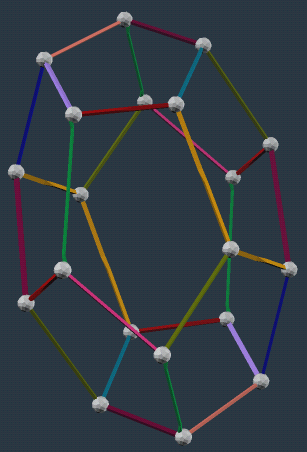

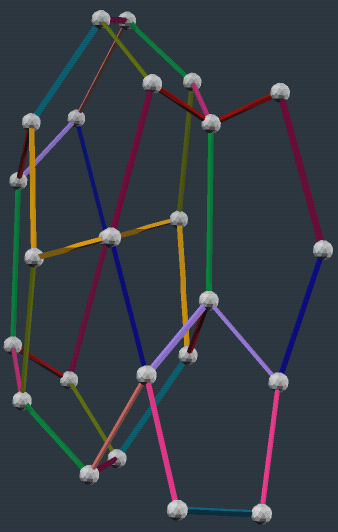

Here's what I got when I applied that strategy to a "flattened" dodec with blue and green edges... an M&M-shaped 120-cell:

|

|

This model surprised me, in that it is mostly comprised of real Zome struts; only the lavender edges cannot be constructed. I'm fairly certain that it would hold together, even without them.

Now, it is a fact that any set of zones that can build the 120-cell can also build any of the other members of the H4 family of uniform 4D polytopes. Taking this thought one step further, you can see that the affine transformation that maps the usual 120-cell to this prolate spheroid can be applied to any model, and if the original model used only red, yellow, and blue struts, the transformed version will use only the red, yellow, blue, green, and lavender struts we see in the figure above. In effect, this represents a five-orbit, alternative Zome-like system, in which everything happens to come out flattened.

The obvious truth is that any affine transformation can be applied to Zome models; it really has nothing to do with constructing pentagons, that's just an intriguing but somewhat backward way of defining an affine transformation. All one really needs is a starting "basis" of three struts, and the transformed version of that basis.

Somewhat less obvious is the implication that any affine transformation produces a set of orbits that are the mapped versions of the red/yellow/blue icosahedral orbits of rZome. It is interesting when that set of orbits is small, or when most of the orbits are "borrowed" rZome orbits, as above. How often does that happen?

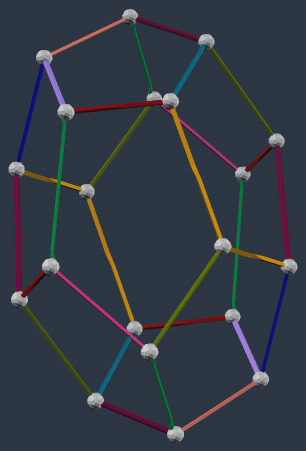

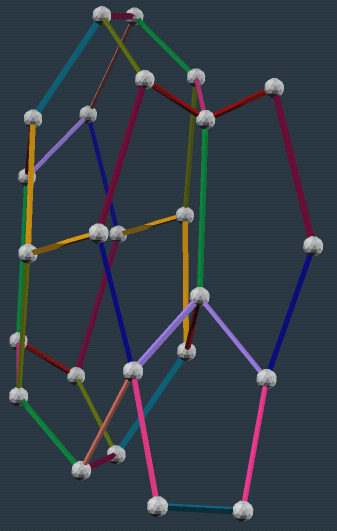

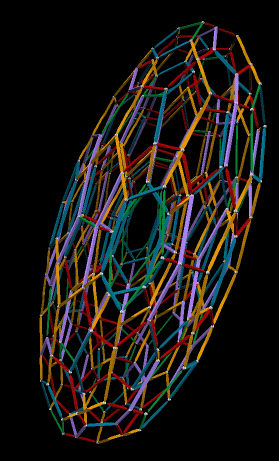

In trying to answer that question, I decided to explore another affine-regular dodecahedron of my acquaintance, this time a stretched one, again using blue and green struts. The result is just as intriguing as the previous one, but this time it is cucumber-shaped, and it uses an orbit of olive struts rather than lavender ones:

|

|

I decided to try to build this one in rZome, since the length scales seemed more manageable than those in the lavender model. I managed most of one end before running out of red, and it does hold together, in spite of the missing olive struts.

Most affine-regular 120-cells you might happen to construct will not be nearly so symmetrical, and will therefore require many more colors. (Building an entire 120-cell one pentagon at a time is painful; only the use of symmetry allowed me to build the two above in reasonable time.) It is difficult, in fact, to create one that does not need any "white" (unknown) orbits in vZome.

There's lot's more to be said, but this is getting long. For example, how do the four starting vectors of our affine-regular 120-cell correspond to the six vectors needed to define a general affine transformation? Or, are the orbits of the symmetry group of an affine-regular 120-cell always a subset of the usual vZome orbits based on H_3 symmetry? Could the colors "lie" to us? Get in touch with me if you have thoughts on these questions.